In the past 20 years, two presidents–George W. Bush and Donald Trump–have won the nation’s highest office without the support of a majority of Americans who voted. You might be wondering how that’s possible in a nation that prides itself on democracy and equal representation. It’s a good question.

The answer lies in that centuries-old system, the Electoral College. It’s a piece of political infrastructure that has come under increasing criticism in recent years from advocates of the “one man, one vote” philosophy. Attempts at its destruction in 2005 and 2016–as well as popular support for more direct democracy–have many Americans scratching their heads and asking the question, “Do we really still need the Electoral College?”

In order to explore that question, one must first take a trip back in time. Doing so will help to explain why the US uses this system in the first place.

The Electoral College was originally proposed by James Wilson back in 1787 at the Constitutional Convention in Philadelphia. The question of how to elect the president was one that plagued the framers for months. While many of the “Founding Fathers” favored using a Congressional vote to choose the nation’s leader, eventually they determined that scenario would not allow for a true separation of powers. Some, like James Madison, favored election by a popular vote.

After much debate, though, they settled on the current system. It allows the people to vote for the president through a group of so-called “electors” that represent them and their votes. This means that under the current system, the American people aren’t actually the ones to decide the election. The popular vote tallies in each state merely serve as recommendations for the electors to consider before casting their state’s votes in the Electoral College, which ultimately decides who becomes president.

In some states, electors are legally required to vote for the candidate that receives the most popular votes. Not all states have these restrictions, though. In the whole of US history, 157 electors have refused to vote for their party’s candidate. This is an extremely rare phenomenon. The Brennan Center for Justice estimates that these lost Electoral College votes only account for about 1% of all Electoral College votes ever cast.

The reason the “Founding Fathers” created this system was to allow for a buffer between the popular vote and the election of the president. If the popular vote favored an unqualified candidate, for example, the electors could refuse to cast their votes along the popular vote lines to safeguard the health of the republic. Historically, though, the Electoral College has served more as a political ritual than a useful tool. Only 5 times in 46 elections has the candidate with a higher national popular vote lost the Electoral College.

Under the Electoral College, each state is allocated a number of electors equal to its number of representatives in the House, plus two senators. California, for example, has 53 representatives and 2 senators, so it gets 55 Electoral College votes. Because the number of seats a state receives in the House is directly proportional to its population, heavily populated states like Texas and New York have a large number of electors. The lowest number of electors a state can have is 3, which is the total elector count in sparsely populated states like Wyoming or Montana.

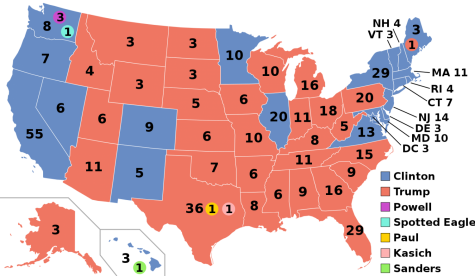

The numbers you see on the maps on television actually denote the total number of electors each state has. All in all, there are 538 electors in the 50 states, and so there are 538 total Electoral College votes up for grabs in each election. The first candidate to receive 270 Electoral College votes becomes the president.

It’s usually clear on Election night–except for this year–who is going to win the presidential election. As states’ popular vote results come in, media outlets like the Associated Press, CNN, and Fox News “call” the race and project who will be inaugurated at the Capitol Building on January 20.

It’s important to remember these are just projections, however. The election is not officially over until the electors cast their votes in the Electoral College and the results are certified by the states.

Before the official votes can be cast, the electors need to be officially chosen. Although each party nominates a group of potential electors months before the election, those electors only become official electors if their party wins the state’s popular vote. In Illinois, for example, a group of 20 democratic electors will become electors and cast their votes for Joe Biden before December 14, 2020. Only then will the state have truly voted for Joe Biden and Kamala Harris.

So, how is it that a president can lose the national popular vote but win the Electoral College? In order for this to occur, the losing candidate must lose a number of relatively electorally rich states by extremely small margins, and win by very large margins in other very electorally rich states. That sounds complicated, so let’s break it down.

For the sake of simplicity, let’s assume the country has only 4 states: Florida, North Carolina, Texas, and California. The following are some hypothetical popular and Electoral College vote tallies:

Florida (29 Electoral College votes)

Candidate A: 6,000,000 votes (wins by 1.67%)

Candidate B: 5,900,000 votes

Texas (38 Electoral College votes)

Candidate A: 8,000,000 votes (wins by 1.27%)

Candidate B: 7,900,000 votes

North Carolina (15 Electoral College votes)

Candidate A: 3,000,000 votes (wins by 3.45%)

Candidate B: 2,900,000 votes

California (55 Electoral College Votes)

Candidate A: 3,000,000 votes

Candidate B: 21,000,000 votes (wins by 69%)

Popular Vote Total:

Candidate A: 20,000,000 votes

Candidate B: 21,000,000 votes

Electoral College Vote Total:

Candidate A: 82 votes

Candidate B: 55 votes

In this scenario, candidate B wins the popular vote but still loses the election. He loses by small margins in a number of states that have a moderate number of Electoral College votes, but then wins by a huge margin in a state (CA) that has a lot of Electoral College votes. So while he’s racking up popular votes in FL, TX, and NC, he’s not getting any Electoral College vote from those states, which makes it impossible to win the election.

Because of this tricky math, the Electoral College system has drawn increasing criticism in recent years. The popular vote lost out to the electoral vote in both the 2000 Bush-Gore race and the 2016 Trump-Clinton election. In 2016, Clinton won the popular vote by 2.8 million votes, yet Donald Trump won the election with 304 Electoral votes. Critics of the system feel such a scenario is a breach of democracy.

Opponents of the Electoral College also argue that it forces candidates to focus a disproportionate amount of time and energy on so-called “battleground” states. These are states that have a significant number of Electoral College votes, but which also have a roughly equal proportion of democratic and republican voters. Because the margins between the number of supporters for each party in these states are so small, it is possible for a candidate to “flip” the state and gain all of its Electoral College votes by increasing his popular vote by a small amount (say, a couple thousand votes).

Doing so often takes a considerable amount of time and effort, though. Critics fear so-called “stronghold” states–states that have voted for one party many times in a row– and their people are forgotten when it comes time to campaign because candidates focus so heavily on the battlegrounds.

Battleground states have featured prominently in the 2020 election. The outcome of the election essentially came down to several of these states–namely Wisconsin, Michigan, Pennsylvania, and Arizona. Biden was able to turn these states back “blue” after they voted for Trump in 2016, and it was ultimately their Electoral College votes that pushed him through to the White House. Races in these states were extremely close, with Biden winning in Wisconsin by just over 20,000 votes and in Arizona by just over 10,000.

Despite the criticism, the Electoral College remains part of the Constitution. Changing it would require a Constitutional amendment, which would be difficult to secure. Direct popular vote would be the most likely alternative to the Electoral College, although other methods have also been explored.

One option is to vote by Congressional districts, as states like Maine and Nebraska currently do in the Electoral College. Under this system, each district would receive a number of electoral votes in proportion to its population. Advocates say a method like this would eliminate the possibility of a candidate winning a large number of popular votes but losing all of that state’s Electoral College votes.

Another option is to keep the Electoral College, but allow states to assign their Electoral College votes proportionally based on the popular vote counts. For example, if a candidate won 70% of the popular vote in a state with 10 total Electoral College votes, he’d receive 7 votes. The other candidate, winning 30% of the popular vote, would earn 3.

But there are also ardent supporters of the Electoral College. These people claim it preserves traditional federalist philosophy, separates powers between the state and federal governments, and delivers definitive outcomes.

In their minds, the Electoral College also forces candidates to build broad support across different regions of the country. Some fear that moving to a popular vote would cause candidates to only campaign in urban centers where there is a high concentration of votes. They argue this would cause people who live in rural areas–which is 19.3% of Americans, according to a 2017 US Census survey–to be forgotten when the time comes to draft policy.

So should we keep the Electoral College? It’s difficult to say. One thing is for certain, however: supporters and critics alike will continue to advocate for their respective positions as we navigate the future of American democracy.