On March 8, the D303 School Board approved the implementation of Deep Equity, a professional development program for teachers, starting next year.

The program aims to reduce educational inequities–meaning differences in learning outcomes–for specific subgroups in the district that are currently underperforming. These subgroups may include Black/African American, Hispanics, students with IEPs/504s, and socioeconomically disadvantaged students, among others.

The district’s approval of Deep Equity’s comes in the wake of the district’s commitment to ensuring diversity and equality in its practices following the death of George Floyd and the subsequent racial reckoning expereinced across the country last summer.

Other Chicagoland school districts, like DuPage High School District 88 and Naperville CUSD 203, have previously partnered with Deep Equity in an effort to reduce educational inequities.

What is Deep Equity?

Deep Equity, according to their website, is a professional development program for teachers, whose goal is to “produc[e] the deep personal, professional, and organizational transformations that are necessary to create equitable places of learning for all of our nation’s children.”

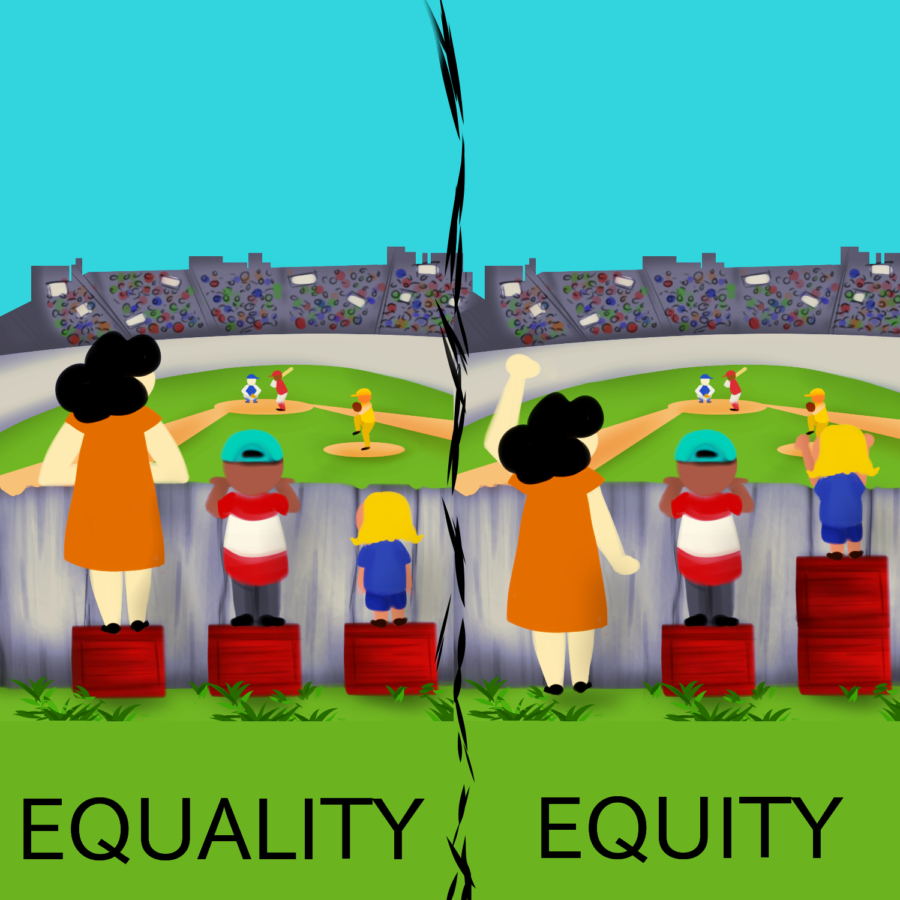

Put more simply, the program is based on the idea that achievement gaps exist for specific subgroups in school districts across the nation, and there is a need to address those gaps.

At the February 16 School Board Meeting, district administrators identified examples of the subgroups that Deep Equity may impact locally. Black/African American and Hispanic were included, among others.

Deep Equity aims to reduce performance gaps in such a way that allows students from these subgroups to achieve at the same level as other students.

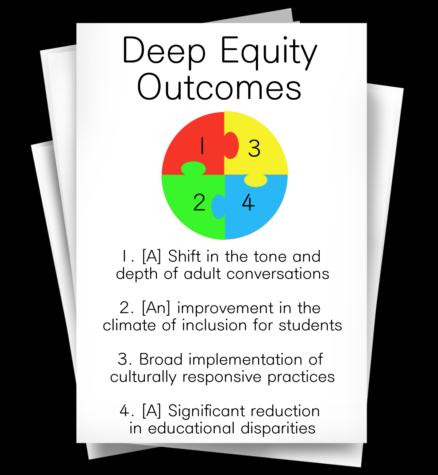

The program presents four key outcomes:

1. [A] shift in tone and depth of adult conversations

2. [An] improvement in the climate of inclusion for students

3. Broad implementation of culturally responsive practice

4. [A] Significant reduction in education disparities

The specific strategies they use to achieve these outcomes vary by district. The program uses a consistent foundational curriculum for all its customers.

Representatives from Deep Equity come to the partner district to present this core knowledge. Through seminars, discussions, and written reflections, teachers learn the content of the following “5 Foundational Phases”, which function like units:

1. Tone and Trust

2. Personal Culture and Personal Journey

3. Social Dominance to Social Justice

4. Classroom Implications and Applications

5. Systemic Transformation/Planning for Change

These phases aim to create trust in equity work, help teachers understand the cultures of students from specific subgroups, and design strategies to be used in the classroom to reduce implicit bias and cultural ignorance.

The idea is that in creating a more welcoming environment for these subgroups, they will engage more deeply with class material, which will translate into better academic performance.

“[Deep Equity] is really about shifting awareness and heighteing mindsets among teachers, who are the ones interacting through the system to demonstrate acceptance, tolerance, and inclusion–or the opposite of those–towards students,” said English teacher Jacob Stewart, who is a supporter of Deep Equity and has participated similar equity training in the past.

“The ultimate goal is to provide equal access and opportunity so that all have the privileges the dominant culture possesses,” he said.

Where did Deep Equity come from?

The most recent push for equity work began early last summer.

On June 4, 2020, the district published a letter written by School Board President Nicholas Manhiem and Superintendent Dr. Jason Pearson: “A Message about Equity, Diversity and Inclusion from D303.”

The letter reaffirmed the district’s desire for equity in light of the death of George Floyd and announced that D303 would reevaluate its curriculum, instructional materials, and classroom practices to ensure they represented diversity.

Out of that commitment to diversity came a new School Board Equity Goal, which aims “to create a culture that supports equity, diversity, and inclusion for CUSD 303 students and staff that reflects our diverse society and develops skills in appreciating differences, overcoming conflicts, and contributing to society.”

During the fall, the School Board examined D303’s educational disparities. Using data from standardized tests like the iReady Assessment and PSAT, they found that some subgroups score significantly lower than others across all grades.

“It’s just glaring,” said Board Secretary Jillian Barker. “When you have such significant gaps between the majority groups and [minority] subgroups, that tells you there are inequities in your system that you need to look at.”

“Our shortcoming is not our capacity to care or love, or that we are systemically targeting and racist. It is that we have implicit bias and cultural beliefs about specific behaviors,” said Stewart. He believes those biases translate into inequity.

The Board then began investigating ways to achieve its equity goal. Eventually, a potential solution emerged. It included a two-part proposal.

The first piece of the proposal allowed the district to create a new administrative position called the “Director of Diversity, Equity, and Inclusion.” This role would be to coordinate and oversee the district’s efforts to eliminate educational inequities.

The second piece of the proposal allowed the hiring of an outside equity consultant to educate teachers about “cultural competency” and how to dismantle disparities. After vetting multiple programs, Deep Equity was selected as the preferred consultant.

On March 8, the Board took a vote and approved both measures.

Why the controversy?

Broadly speaking, opponents have two major concerns about the program.

The first concern is that Deep Equity guilts whites for their privilege and labels them as the “oppressors” of minority subgroups. Because of this, opponents believe it will backfire and cause greater tensions between racial groups in St. Charles.

“[Deep Equity] is very controversial because the way that it’s done sheds a lot of guilt on growing up with white privilege, which most of us in this community have,” said Mark Huber, president of the parent advocacy group Parents 4 Progress. Huber supports equity in general, but not Deep Equity specifically.

“We have some pretty strong willed people in this community, and if [equity work] is not handled tactfully, we’re going to have a huge problem, because it’s going to be resisted,” he said.

Deep Equity, for its part, rejects the notion of guilting its participants.

“I can honestly say that I have never once had a participant come with a concern expressing that [Deep Equity] felt like shame and blame,” said Trudy Arraiga, a Deep Equity representative, during a February 16 presentation to the D303 School Board.

Barker–who, like the rest of the Board members, was given access to the totality of Deep Equity’s materials before the March 8 vote–likewise dismisses the idea of shaming.

“Lots of people will bring resistance to equity work. But there’s activities and discussions that are meant to help people see that there won’t be any shame or blame and they don’t have to be afraid to bring whatever their truth is to the table,” she said.

The second concern opponents have with Deep Equity has to do with the program being perceived as vague, and therefore its effects being difficult to track.

During their February 16 presentation to the School Board, some board members felt that the Deep Equity representatives had difficulties explaining what the program concretely involves. When pressed, they also seemed to struggle to present evidence that their work has led to statistical improvements in districts with similar demographics to D303.

This led some on the Board to believe they didn’t have enough information to vote on March 8. Edward McNally, who voted against Deep Equity, expressed concern that the Board was moving too fast towards approval.

“I don’t want to rush into [the] program because if we find out in 3 years that it’s a big failure, those kids don’t get to go back and make up those three years,”he said.

“Deep Equity, I think, is primarily about profit,” said Huber. “I’m concerned that the $100,000 we’re spending up front is going to turn into $200,000 or $300,000, because they’re going to tell you there’s no real way to gauge the success of this thing. It’s a slow cultural shift. In the meantime, they’re continuously upselling you on a variety of different, more expensive programs.”

To be sure, the controversy surrounding Deep Equity is an ongoing discussion. In the coming days and months, more about the program will be revealed as D303 begins to make headway towards its equity goal.

( Note: Jacob Stewart, who features in this story, is one of the advisors to The X-Ray. He did not, however, have any involvement in the initiation, writing, or editing of this article.)