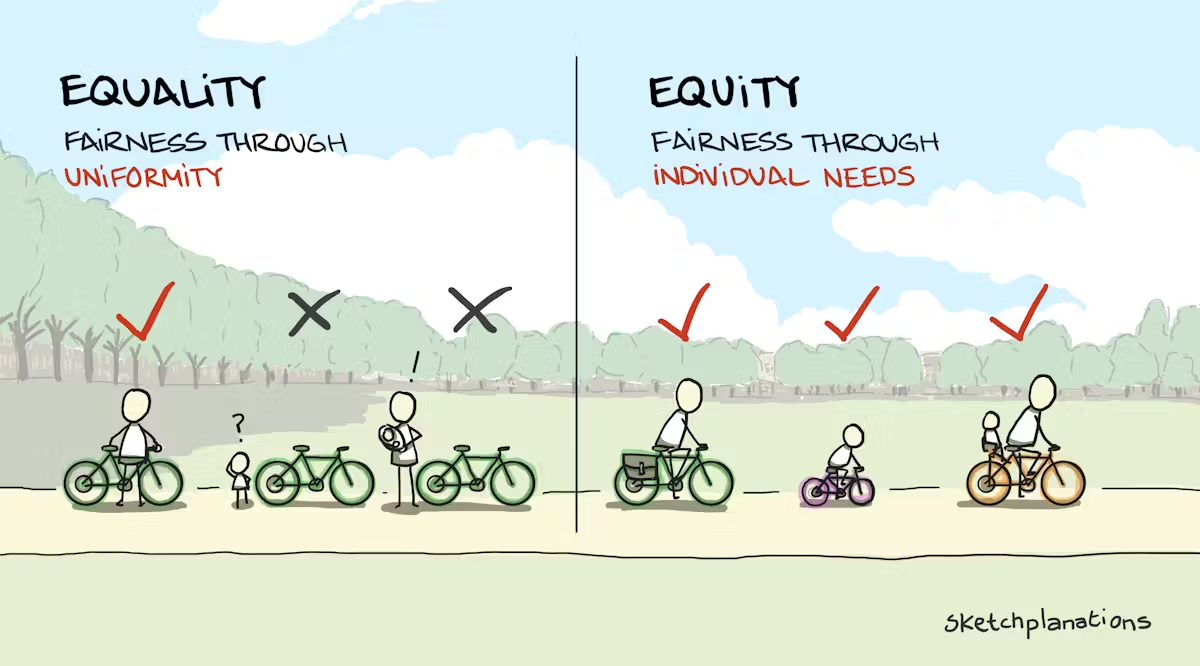

We live in a society where discussions of mental health have become normalized. Constant displays of advocacy for mental health awareness flow through recommendation pages on social media.

Advertisements on billboards, posters, and TV tell us, “It’s okay not to feel okay.” The presence of these reminders may offer a sense of clarity and help others feel less alone in their mental health journey. Despite this, some athletes have found that this encouragement lacks the support it intends to have.

St. Charles East has a heavy focus on our athletic programs. At freshman orientation, Athletics Director Mike Sommerfield tells incoming freshmen the success stories of athletes who have achieved greatness at East, including our several state championships, asking students if they will be the next to get our school another plaque. Needless to say, it seems almost impossible not to participate in a sport at East. Hundreds of students at East “balance” schoolwork, sports and extracurriculars on the daily. The countless hours spent weekly on practice, homework, activities and work cause lots of stress in the student-athlete community.

In a survey conducted by X-ray on the mental health of student-athletes at East, 77.7 percent of survey participants stated that they spend anywhere from six to seven days a week practicing for their sport, with an average of two and a half hours spent at practice each day. This means that students often come home anywhere between four and five in the afternoon or later, depending on games, matches, or meets. Most coaches will tell their athletes, “Student comes before athlete.” Certain standards are set for students to be able to participate in their sports, specifically, keeping up with what are considered to be passing grades. Jayna Oriente, a sophomore who runs for East’s Girls Track and Field team, spends three to six days at practice alongside hours of homework every week. “Balancing sports with school is a life skill, to be honest,” Oriente reflected. “Time is everything when it comes to this and understanding priorities is a major thing too.”

66.7 percent of student-athletes who took the survey described how they often procrastinate on their homework because of their sport, with a whopping 22.2 percent describing how they always procrastinate because of the time spent practicing every day.

“[Sports have] definitely made me procrastinate more and become an overachiever,” said an anonymous athlete. “I have gotten backed up with homework, which makes me super stressed. I get overwhelmed.”

With so much time spent on academics and perfecting physical performance on and off the field, finding time to spend with friends and family can be hard. “I can never do anything like hang out with my friends,” said an anonymous spring sport athlete. Despite it seeming almost impossible to socialize outside of practice, sports have also allowed athletes to meet new people and become friends with their teammates. “You make lifelong friends; you build skills in leadership and character,” said former basketball player Cecilia Call.

On Nov. 14, former basketball coach Mark Potter presented his “Mental Health Matters” presentation in the Norris Cultural Arts Center in front of dozens of student-athletes at East. During the presentation, Potter discussed his mental health struggles and how he persevered through his own mental battle with the help of his wife, Nannette Potter, and medical professionals. He mentioned how he “hid behind closed doors” and “put on a mask” as a way to hide his mental state from his athletes and those closest to him. Once he talked to his wife about his problems, he took action to help himself get better and back to the best version of himself. His mental health journey inspired him to talk to athletes across the country about ways to “shatter the stigma” against the tough standards student-athletes are held to so that they “don’t suffer in silence.”.

Students who attended the presentation reflected on what they took away from Potter’s speech. “The worst thing to do is nothing,” said an anonymous cross-country and track runner.

As mentioned in Potter’s speech, the stigma surrounding student-athlete mental health is real. According to nih.gov, one in five student-athletes experience some sort of mental health concern in their sport, while only half of those students get treatment. While getting treatment may seem difficult, there are ways to help combat mental health struggles in sports.

It all starts with reaching out to somebody. Tessa Muenz, a sophomore, described her way of reaching out when she needs support. “[My] teachers, coaches and friends…they have helped a tremendous amount; allowing me to learn my best and to run my best while at my worst,” said Muenz. “Coach Kaplan is genuinely the most amazing coach and person I have ever met in my whole entire life. If we email him and tell him that we are having a hard time, he will, without [a] doubt, always check on you and help you in any way he can. All of his efforts have made me who I am as a person and an athlete.”

Despite East’s efforts to help the student-athlete, there are still many ways in which the stresses of school and sports can be lessened. “We should get rid of gym [class] for student-athletes,” said Savannah Jackson, a junior student-athlete at East.

“I wish the school talked more about [mental health] because athlete mental health really does matter [and] it’s something that isn’t talked [about] as much,” said Oriente. “I feel like it’s because most people are uneducated on [the topic] or athletes feel that they’re afraid to share out their experiences.”

As someone who joined the student-athlete community my freshman year, playing sports has given me some of my closest friends and opportunities for growth that I couldn’t find anywhere else. Being in a sport has given me the grit to push through challenging tasks and achieve greatness. Sure, some difficulties come along with being a student-athlete, but they teach you some of the most important lessons you will ever learn.

Regardless if you are a student-athlete or not, it’s okay not to feel okay. Never hesitate to ask for help. The worst thing to do is nothing.